Kevin Warsh floated plenty of ideas for how he would run the Federal Reserve during his campaign for the job as chair. For Wall Street, few are as cryptic — or potentially consequential — as his call for a new accord with the Treasury Department.

Warsh has voiced support for overhauling the relationship between the two institutions with a new version of an agreement struck in 1951.

That pact had dramatically limited the Fed's footprint in the bond market — something that's not true today, after trillions of dollars of securities purchases during the global financial and Covid crises. So when President Donald Trump nominated 55-year-old Warsh as his next Fed chair, investors began to debate just what he intends.

Neither Warsh nor Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has detailed what they may consider after the former Fed governor takes the helm. The nominee did say in a CNBC interview last year that an agreement could "describe plainly and with deliberation" what the Fed's balance-sheet size would be, with the Treasury laying out its debt-issuance plans.

A revamp could prove to be just a bureaucratic tweak, with little near-term impact for the $30 trillion Treasuries market. But a more ambitious effort involving a shake-up of the Fed's current, $6 trillion-plus securities portfolio could see

Looming over any Fed-Treasury talks would be Trump, who last year argued that one of the central bank's duties in setting interest rates is to mind the government's

"Rather than insulating the Fed, it could look more like a framework for yield-curve control," Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors, said of an accord. "A public agreement that synchronizes the Fed's balance sheet with Treasury financing explicitly ties monetary operations to deficits."

And that was exactly what the

Warsh last April

Warsh, contacted through the Hoover Institution where he has served as a fellow, didn't respond to a request for comment on a potential Fed-Treasury accord. The Treasury also didn't respond.

Skinny Version

Bessent has similarly blasted the central bank for sticking with such quantitative easing for too long, saying it even damaged the market's ability to give off important financial signals.

The Treasury chief, who oversaw the vetting process to choose a successor to Jerome Powell, has argued for Fed QE "in true emergencies and in coordination with the rest of government."

So a new accord could simply spell out that — outside of day-to-day liquidity management — the Fed would only make large-scale Treasuries purchases with the Treasury's endorsement, with an eye to halting the QE as soon as market conditions allowed.

But inserting the Treasury into Fed decisions in such a way could prompt other interpretations. Krishna Guha at Evercore ISI said, "investors will read this as implying that Bessent will have a soft veto" on any quantitative tightening plans.

Bessent

"I wouldn't expect them to do anything quickly," he said. "They've moved to the ample-regime policy, and that does require a larger balance sheet, so I would think that they'll probably sit back, take at least a year to decide what they want to do."

Warsh "is going to be very independent, but mindful that the Fed is accountable to the American people," Bessent said.

A meatier version of an accord would lay out what many market participants expect: A rollover of Fed Treasuries holdings from mid- and longer-tenor securities to bills, which mature in 12 months or less.

That would then allow the Treasury to scale back sales of notes and bonds, or not boost them as much as otherwise. In its quarterly statement on debt management on Wednesday, the department drew a link between Fed actions and its issuance plans — saying it was keeping an eye on a recent step-up in purchases of bills by the central bank.

"We're already heading down that path" of closer Fed-Treasury coordination, said Jack McIntyre of Brandywine Global. "The question is whether it gets magnified."

The risk: Investors view the Fed's actions as moving it away from its inflation-fighting mandate, increasing prospects for higher volatility and inflation expectations. A worst-case scenario might see an undermining of the appeal of the US dollar and safe haven status of Treasuries.

If there's an accord that "implies that the Treasury can count on the Fed buying some portion of the debt or on some portion of the curve for the foreseeable future, that's hugely, hugely problematic," said Ed Al-Hussainy, a portfolio manager at Columbia Threadneedle Investments.

Some Doubts

Warsh, who could take the helm in May if he's confirmed ahead of the expiration of Powell's term as chair, may seek to avoid any such outcome.

"Warsh will be committed to keeping the Fed separate," said Mark Dowding, chief investment officer at RBC BlueBay Asset Management. "That does not rule out greater collaboration, but it makes a formal accord less likely."

Others have laid out expansive scenarios where the Fed is one part of a multi-step initiative to revamp federal authorities' imprint in the bond market.

Guha, Evercore ISI's head of central bank strategy, has floated the idea of the Fed swapping its $2 trillion mortgage bond portfolio with the Treasury Department, in exchange for bills.

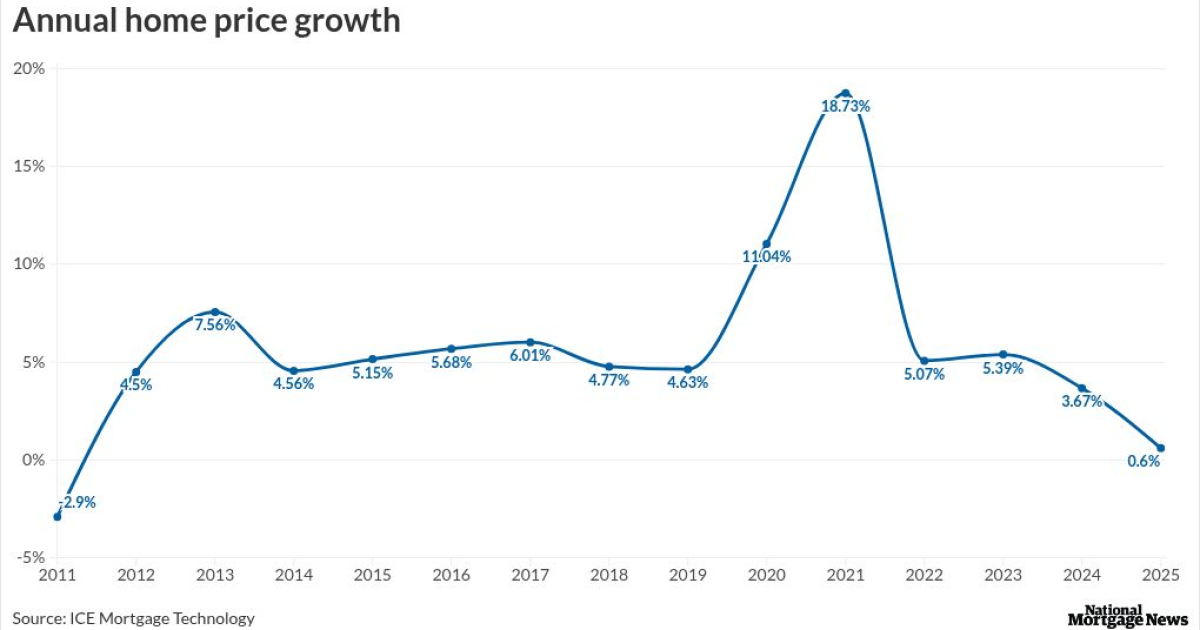

While that poses several hurdles and may ultimately prove unlikely, one goal could be to lower mortgage rates — a key focus of the Trump administration. The president last month directed government-controlled Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy

A new accord could "provide, over time, a framework for the Fed working in tandem with the Treasury – and perhaps also with the housing agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – to shrink the size of its balance sheet," wrote Richard Clarida, a global economic adviser at Pacific Investment Management Co and former Fed vice chair.

Portfolio Shift

Warsh would almost certainly be unable to do a deal with Bessent on his own. But some current Fed policymakers have backed the idea of shifting the central bank's portfolio to bills and argued that its heavy exposure to long-term assets no longer reflects market structure.

Deutsche Bank strategists predicted that a Warsh-led Fed would likely be an active buyer of Treasury bills for the coming five to seven years. In one scenario, they see T-bills rising to as much as 55% of its holdings, from less than 5% now.

A commensurate shift by the Treasury to sell bills rather than interest-bearing securities wouldn't be cost-free, however. With a giant amount of debt constantly rolling over, it would increase the volatility of the Treasury's borrowing costs.

With or without an accord, market participants are on watch for a tighter relationship between the Fed and Treasury when it comes to the bond market. And while the aim might be to limit the interest costs to all types of American borrowers, any fundamental shift has its dangers.

Outright coordination to damp interest costs "might work for a while," said George Hall, an economics professor at Brandeis University and a former Chicago Fed researcher. But in the long-run, investors have alternatives to US assets.

"People will figure out ways around that, and over time will take their money elsewhere," he said.