With a war waging in Central Europe, inflation at 50-year highs and the U.S. central bank looking to raise interest rates multiple times this year, you’d think that the average mortgage banker already has a pretty full plate. But add to the list of woes the Fed’s abortive transition from Libor to the Secured Overnight Financing Rate or SOFR and you have a recipe for disaster later this year.

While many participants are starting the transition, the bank-funded 30-day securities repo and collateral financial markets are not changing. Not even close. Of some 60 bank warehouse lines this banker has personally reviewed, only one has attempted to move to SOFR. None of the others are even contemplating a change in 2022.

So what is the problem with SOFR? Why is SOFR being shunned by bankers? In the words of a senior commercial warehouse lender: "Using SOFR to price bank loans is unsafe and unsound. There is no SOFR term market. You cannot hedge or observe the forward rate."

In a nutshell, SOFR is a concept in search of an actual market. Keep in mind that the Fed and Bank of England largely fixed the technical problems with Libor a decade ago, but then decided in a fit of regulatory displeasure to kill the market for pricing global dollar transactions without first identifying a viable replacement. This fact forced the Fed to delay SOFR implementation. It will be delayed again unless a lot changes.

"At the end of 2020, the Intercontinental Exchange announced that ICE Benchmark Administration Limited — the administrator of the London Interbank Offered Rates — had consulted on its intention to cease the publication of the one, three, six and twelve- month U.S. Dollar Libor by June 30, 2023, instead of the original discontinuation target date in December 2021," notes Oscar Stephens of Greenberg Traurig in a comment entitled "Disaster Averted."

But has the disaster been avoided or merely delayed? Why not simply fix the existing Libor? Well, that would require the folks at the Fed, BOE and other central banks to admit that they were wrong to kill the benchmark in the first place. Probably not a good idea. But fashioning a new, functioning market benchmark is even less easy.

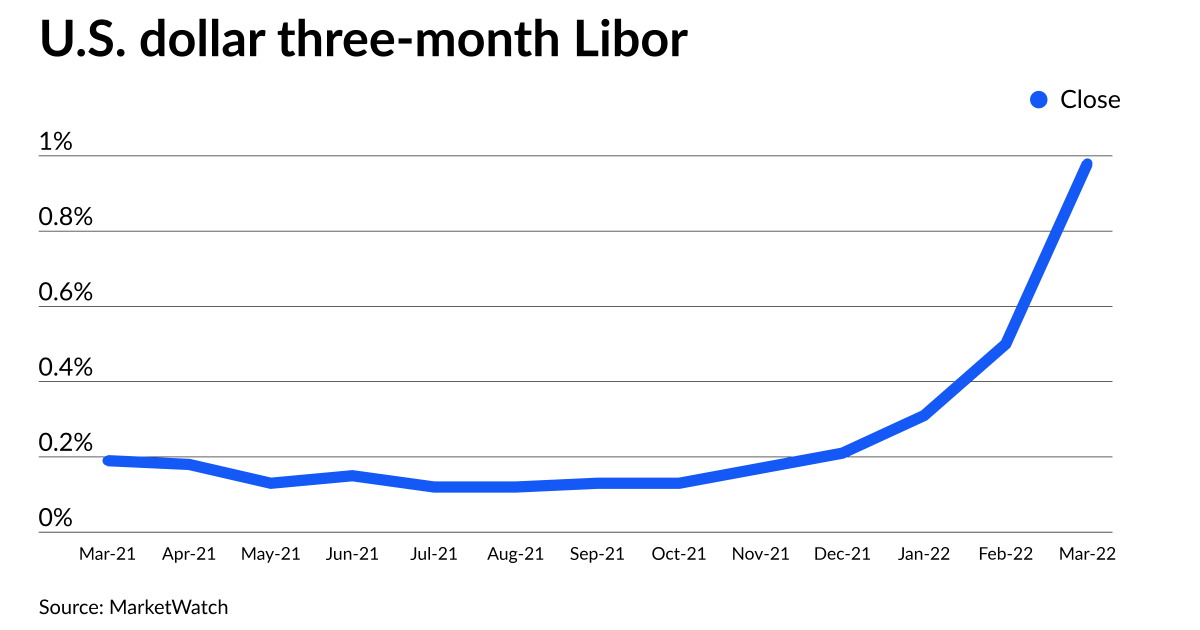

SOFR truly is a disaster from a risk and market perspective since there is very little trading activity and the existing volumes are artificial. SOFR does not actually move with interest rates such as Federal Funds, Libor, to-be-announced (TBA) trading or other benchmarks. Why would the Fed and BOE deliberately inject new risks into the financial system for no apparent reason? Somebody in Congress should ask Chairman Jerome Powell that question.

Traders and lenders have been forced to manually adjust the pricing of new loans and securities that use SOFR. Trustees are also faced with a similar dilemma in transforming floating rate securities originally priced versus Libor to instead use SOFR.

Let’s take an example. Say you want to swap 3-month Libor into 3-month SOFR. The party paying in SOFR must add 30 basis points to the trade as of the close on Friday. This writer has seen similar price adjustments in the market for commercial real estate and collateralized loan obligations, which all historically priced off of Libor.

What the markets are telling us, using data from Bloomberg Markets, is that SOFR is not a very good benchmark for investors to use to price securities or loans. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in providing guidance about the transition to SOFR, talked about adding a "spread" to SOFR transactions to make up for the difference.

But wait a minute, isn’t the whole point of a benchmark like Libor and SOFR that we don't have to make manual adjustments to the rate?

The Fed's decision to kill Libor was an entirely retrograde step that lacks logic and frankly due diligence. The folks at the Fed never bothered to ask if creating a new market for short-term US funds was even possible before making the decision to kill Libor.

Since SOFR is an artificial overnight rate and does not yet have a true market following (aka "markets, people"), including a term structure out even 30 days, warehouse lenders and other providers of cash to the markets are not moving as yet. Memo to Chair Powell: How can a federally insured depository use a nonexistent benchmark like SOFR to price assets and liabilities?

In the Libor transition timeline published by the Few York Fed, the central bank declares that a there should exist a "forward-looking SOFR term reference rate by the end of 2021 H1." A year later, there is still no term structure for SOFR. If you look on Bloomberg, for example, the only rate for SOFR is overnight and there is no term structure as with Libor or the Treasury swaps and yield curves.

Ironically, Bloomberg just received approval for an index that represents interpolated curve for SOFR, but no actual forward market exists. The lack of liquidity in SOFR beyond overnight trading presents a number of serious problems for the financial markets, not just financial institutions.

First and foremost, the lack of correlation between Libor and SOFR raises a basic question as to whether any investor, bank officer or fiduciary should employ the rate. If SOFR does not reflect changes in interest rate policy by the FOMC, why should anyone use it? Should a mortgage lender, for example, use SOFR-plus to price loans?

Second, how can a bank or non-bank manage SOFR market risk if the benchmark does not move with other interest rates? How does one hedge a SOFR rate exposure? Chairman Powell has not addressed this issue in his comments to Congress, but it is certainly an important topic.

More important, if you are an issuer or trustee that must adjust a Libor-based loan or security to SOFR, just how is this to be accomplished? Do we, say, substitute SOFR-plus 30 bps for the Libor rate? What happens when a borrower or investor objects to the substitution and decides to sue us for fraud? Do we sue the Federal Reserve Board as a third party and seek contribution for the claim?

Because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there has been recent activity in the spread between SOFR and Eurodollars out to December 2023, a remarkable fact given that there is zero trading in SOFR for tenors of two years. By that time, U.S. banks are meant to be pricing warehouse lines and repurchase agreements for 1-4s in SOFR.

Our best guess based upon the abysmal performance of SOFR to date is that by December 2023 the Fed's creation will still be struggling to find a real market following and U.S. banks will still be pricing warehouse lines, advance facilities and gestation trades off of 30-day Libor or some other benchmark. Perhaps by then, Chairman Powell can explain to Congress why he decided to terminate Libor without having a ready replacement in hand.

"While market participants expected Libor would not be available beyond 2021, concerns about market readiness for the transition remain," wrote Debevoise and Plimpton last year. That may be the understatement of the decade.