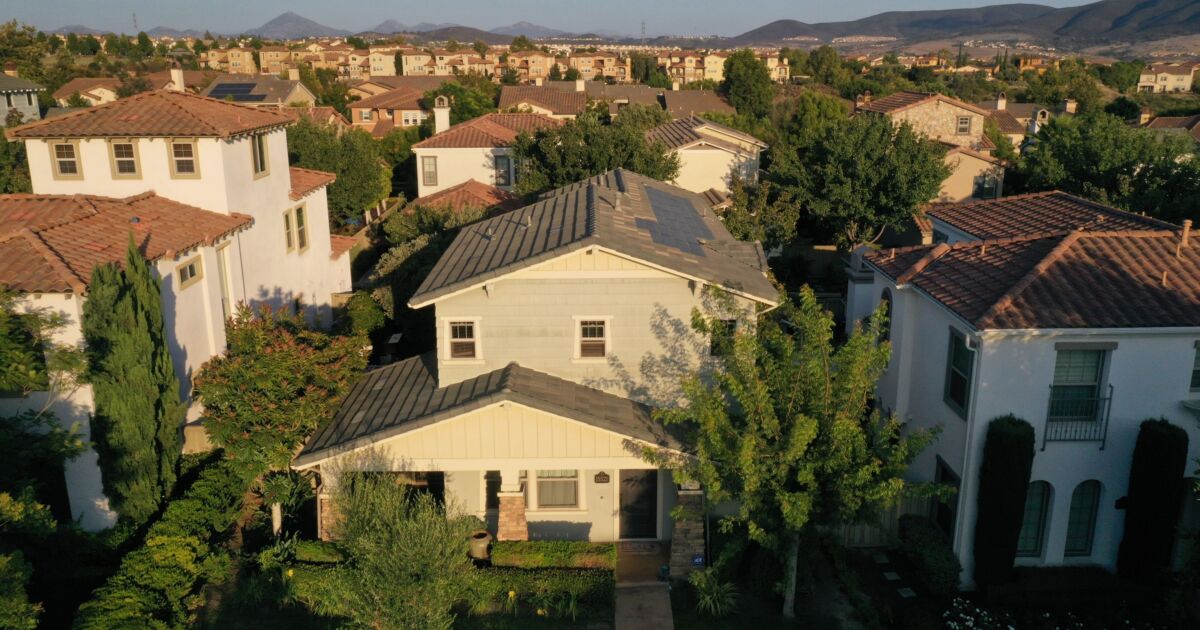

First-time home buyers entering the market today are in for a rude awakening. Having watched as mortgage rates fell to historic lows in recent years, fueling increases in home prices, homebuyers are now confronted with a double whammy. Mortgage rates have skyrocketed, while prices remain sticky, falling a bit in some markets but not nearly enough to offset the significantly increased cost of a mortgage.

Mortgage rates have almost tripled compared to the low-water mark almost three years ago. According to the St. Louis Fed, the 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the U.S. as of Sept. 28, was 7.31%. On Dec. 17, 2020, the same index was at only 2.67%.

This has a significant negative effect on the ability of a family to buy a home, particularly for first-time home buyers — and has made it much harder to qualify for a mortgage in order to do so. Data from the National Association of Realtors has shown that skyrocketing mortgage rates have played a key role in a 15.3% decline in home sales in August 2023 compared to a year ago. Both developments are bad for economic growth and bad for our housing and mortgage markets.

High mortgage rates also make it extremely costly for mortgage servicers to pull older low-interest loans out of mortgage pools to execute loss mitigation actions, like partial claims, to keep defaulted homeowners in their homes. To its credit, the Federal Housing Administration recently tried to avoid servicers having to take older low interest loans out of pools to execute loss mitigation. However, this need still exists. Unnecessarily high mortgage rates create disincentives for servicers to take such loss mitigation actions and exacerbate losses for servicers that take such actions.

Understandably, the 2020 mortgage rate levels could not be sustained. Several factors created this historically low point, including the Federal Reserve buying mortgages and COVID-19 depressing economic activity and causing widespread job losses. A significant runup in interest rates — and correspondingly higher mortgage rates — was inevitable as the Fed made the reasonable decision to change overall monetary policy by raising interest rates to address a surge in inflation.

The Federal Reserve's current monetary policy has been directed at taming inflation, even as that has resulted in short-term rates at 22-year highs.

However, the spread between 30-year fixed rate mortgage rates and other long-term interest rate benchmarks is alarming. Over the last decade or so, mortgage spreads between 30-year fixed rate mortgages and 10-year Treasury rates have averaged around 170 basis points (1.7%). Today, they are near 300 basis points. This means that mortgage rates are 125 basis points (1.25%) higher than they should be.

The chief reason for this dramatic increase is simple: the Fed stopped buying long-term mortgages. With duration risk keeping other buyers sidelined, there exists a classic supply and demand imbalance.

This spread between mortgage rates and 10-year Treasuries will eventually narrow when the Fed finishes its current course of monetary tightening. But housing and mortgage markets need relief now.

So, we have one simple request from the Fed: step back in to buy long-term mortgages now.

If it made sense for the Fed to do this when mortgage rates were at 3%, how can it not make sense to do so now, when mortgage rates are over 7%?

This will not compromise the Fed's campaign to kill inflation in its tracks. Moreover, we understand the Fed is already buying long-term debt instruments from banks. The Federal Reserve's goal of reducing inflation is done through actions influencing the short end of the yield curve, not the long end. Since mortgage spreads are simply out of whack, a targeted adjustment is clearly in order.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac used to hold significant levels of their own mortgages in their portfolios. But since their conservatorship, Treasury capped these purchases under the preferred stock purchase agreements.

We are not calling for a return to pre-2008 policies. However, if there was ever a time to amend the PSPAs to allow Fannie and Freddie to be buyers of mortgages, albeit on a temporary basis, it is now. Everyone expects rates and spreads to decline; so concerns about interest rate risk are very limited, and chances are the GSEs would make a profit by doing so.

The health of our economy depends on taming inflation. But it also depends on healthy housing and mortgage markets. With the right policies we can achieve both these objectives.