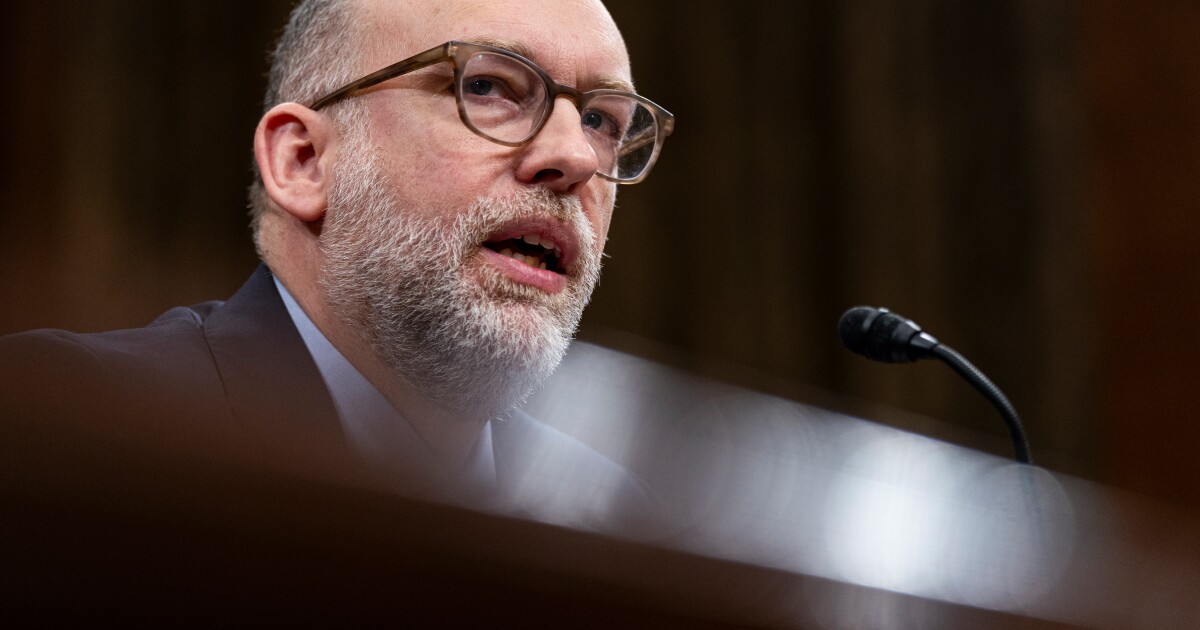

Acting Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Director Russell Vought is waiting for an appeals court to give him the go-ahead to fire roughly 1,500 CFPB employees. If the court rules in favor of the Trump administration, the CFPB will be whittled down to just 200 employees enforcing 18 consumer protection laws.

That scenario has prompted some legal experts to question whether prudential regulators, state attorneys general and state banking agencies will be able to give consumers similar protections in the absence of a full-force CFPB. Under Vought, the CFPB has retracted final rules and

After Vought laid out the CFPB's new priorities under the Trump administration, legal experts warned about the risks from crypto firms and nonbanks that are moving into the financial payments space. In April, the CFPB said it has dropped oversight of all nonbanks and Big Tech firms, and is no longer doing

"States are doing to do what they can — when they have a willingness to do so — but there are only a few states that have an interest and they don't have the resources, manpower and budget to really do it," said Christopher Willis, a partner at Troutman Pepper. "The overall level of regulatory scrutiny and pressure on the industry is going to take a massive reduction over the next several years."

In some ways, the regulatory world is reverting back to what it was like before the 2008 financial crisis and the passage of Dodd-Frank in 2010 — the bill that created the CFPB. Banks and credit unions are covered by their own prudential regulators and nonbanks are covered by the Federal Trade Commission and the states.

"The concern is that such a system could have gaps, which was made evident in the runup to the Great Financial Crisis," said Mark McArdle, former assistant CFPB director of mortgage markets and senior vice president of regulatory affairs and public policy at Newrez, a mortgage lender and servicer in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania.

Earlier this year, former CFPB Director Rohit Chopra

"What's been happening is that the policy pendulum has been swinging wildly for the CFPB's entire life," said Eric Mogilnicki, a partner at Covington & Burling LLP. "The whole rationale for the CFPB was to consolidate consumer protection in an agency apart from the prudential regulators."

Under Vought, the CFPB has

Other experts think the Federal Trade Commission is the most logical choice to step into the fray left by the CFPB. The FTC's consumer protection division is run by Christopher Mufarrige, a former advisor in the first Trump administration to former CFPB Director Kathy Kraninger.

Mufarrige said in an email to American Banker that the FTC is "being very aggressive" and is expanding its fintech and financial services footprint.

Mogilnicki compared the current FTC leadership to Kraninger, who filed a large number of lawsuits focused on intentional fraud and refrained from chasing what he called "good faith mistakes by financial institutions."

"Both Chair Andrew Ferguson and Bureau Director Chris Mufarrige are committed to consumer protection," he said.

But devolving consumer protection to the FTC's smaller staff, which has no supervision of examination authority, "means enforcement is inherently less predictable — more episodic than systemic — which can create uncertainty for businesses trying to operate in good faith without the benefit of clear, ongoing regulatory engagement," said Jonathan Pompan, a partner at the law firm Venable LLP.

Moreover, Congress defanged the FTC decades ago in response to complaints by business interests of regulatory overreach — a strikingly similar reaction to the business community's complaints against the CFPB. Congress passed legislation in 1975 and 1980 restricting the FTC's authority. In 2021, the Supreme Court restricted the FTC's ability to seek monetary awards like restitution or disgorgement from financial institutions, another major setback for the agency's power.

The FTC has very little market monitoring and research capabilities and no authority to compel institutions to respond to consumer complaints, said Diane Thompson, deputy director at the National Consumer Law Center and a former senior advisor to Chopra.

"The FTC can do a lot of good," said Thompson, "but it doesn't have the tools to do what the CFPB was created to do."

Pompan said that no one wants to be the company that ends up as the FTC's test case.

"Inquiries are rarely painless," he said. "The process can be time-consuming, disruptive, and costly, and if it does culminate in a public action, the reputational fallout can far exceed the legal exposure."

Prudential regulators — including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Reserve — could pick up some of the slack, but are unlikely to do so under the Trump administration, several attorneys said.

"The OCC and the FDIC will do something, but it would be a shadow of what the CFPB was doing the last four years," Willis said. "It wouldn't be even close. It would be 10% of what the CFPB was doing in the last few years."

Maria Vullo, former New York Superintendent of Financial Services who runs her own consulting firm, said that federal bank regulators still have consumer protection jurisdiction, "but whether or not the FDIC, OCC and Federal Reserve will exercise it remains to be seen."

Prudential regulators are focused on other priorities under the Trump administration, namely adjusting the

"It's still going to be only those states that believe in consumer protection — so you're going to have most likely the Democratic attorneys general fill in some of the gaps," Vullo said. "The problem with that is that consumers in other states are not going to get the benefit."

Moreover, Democratic state attorneys general have their hands full suing the Trump administration over various policies and executive orders including challenging birthright citizenship and immigration policies; withholding public health funding and dismantling the Department of Health and Human Services; and cutting the federal workforce and trying to overhaul federal elections through an executive order, among other issues.

Among the states, New York State's Department of Financial Services and California's Department of Financial Protection and Innovation are most well-suited to bring consumer protection cases against financial firms. In March, New York's DFS hired Gabriel O'Malley, the CFPB's former deputy enforcement director for policy and strategy, as executive deputy superintendent of consumer protection and financial enforcement.

"It really is kind of down to California and New York to be the cops on the beat," said Casey Jennings, a partner at the law firm Sewell & Kissel and a former CFPB counsel in the Office of Regulations. "The CFPB was such a big hammer because they were well-funded and well-staffed. Banking commissioners aren't and they used to rely on the CFPB to do it."

Apart from enforcement, a main concern is that if the CFPB's staff is cut as dramatically as Vought prefers, there will be a lack of supervision and examinations of large banks. Most CFPB employees are bank examiners, Jennings said, and a 90% reduction in force would inevitably cull their ranks at the agency.

"That's where the hit is," he added. "We've never seen anything like this."

Consumer financial services law, however, remains unchanged. Even so, without routine supervisory engagement or consistent agency guidance, Pompan said, "it's harder to benchmark expectations, and companies are left with broad enforcement powers and to read between the lines of past enforcement actions that may reflect one-off priorities rather than durable policy positions."

State legislators also could pass laws restricting financial products and services.

For example, California, Colorado and New York have laws prohibiting medical debt on credit reports — an idea the CFPB under Chopra

Banks and mortgage lenders want a functioning regulatory system with agencies providing formal guidance so that the industry knows how to comply, experts said.

"The rules are still on the books, the statutes are still on the books, and the states are still doing their jobs and nonbank companies in states with regulators that are fairly aggressive still have to worry," said Willis. "But unfortunately, there are probably a lot of companies out there that think they can do whatever they want."