The Supreme Court on Friday overturned a major legal precedent requiring judges to defer to federal regulatory agencies' interpretation of ambiguous statutes. The 6-3 ruling reduces the power of a wide range of executive branch agencies, including bank regulators, to interpret laws.

The 40-year-old legal doctrine — known as Chevron deference, named for the 1984 Supreme Court decision in Natural Resources Defense Council v. Chevron establishing the precedent — had long frustrated companies in regulated industries because it limited their ability to sue agencies over their interpretations of broad or vague legal authorities.

The doctrine often meant that regulators could write broader, more costly rules than regulated companies believed were warranted. Its demise is expected to open the floodgates to a wave of litigation challenging such rules.

But the end of Chevron deference could be a double-edged sword for banks, according to industry lawyers, because the Supreme Court's decision will also make it easier for advocacy groups and state attorneys general to challenge rules they oppose, which would introduce more uncertainty for banks.

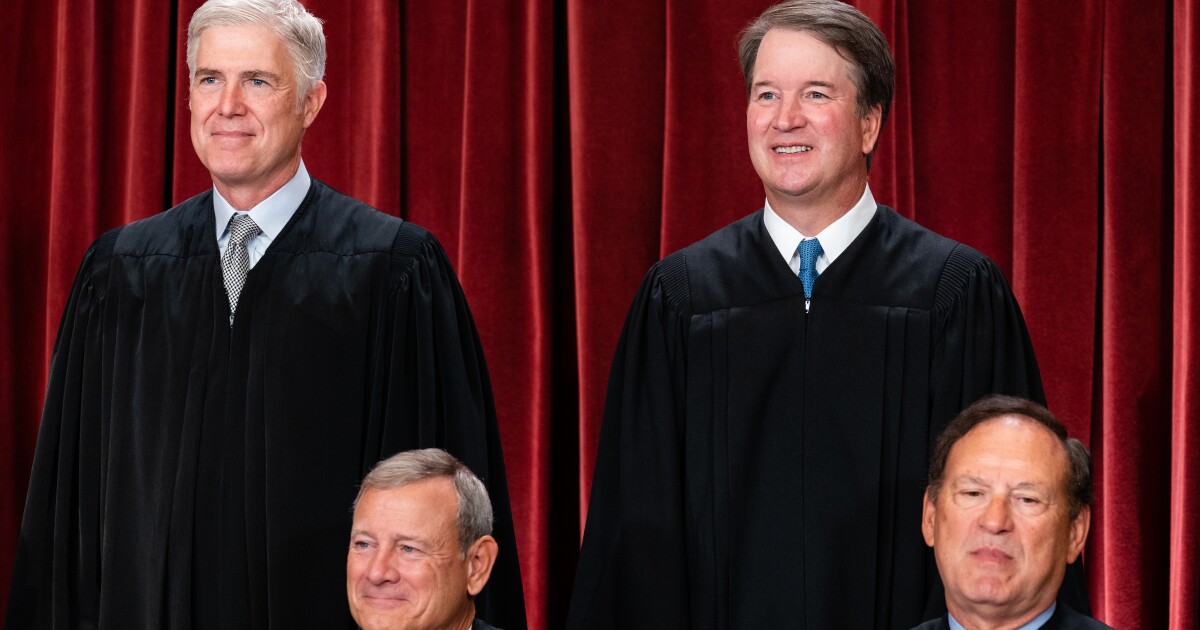

The ruling by the high court's conservative majority, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, held that the Administrative Procedure Act requires courts to exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority. Courts have the option to defer to an agency's interpretation of an ambiguous law, but the court said the firm requirement that it must is incorrect.

"The deference that Chevron requires of courts reviewing agency action cannot be squared with the APA," Roberts wrote. "Perhaps most fundamentally, Chevron's presumption is misguided because agencies have no special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities. Courts do.

"Chevron has proved to be fundamentally misguided," he continued. "And its flaws were apparent from the start, prompting the Court to revise its foundations and continually limit its application. Experience has also shown that Chevron is unworkable."

The court's decision encompassed two cases: Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce. The cases involved fishermen in New Jersey and Rhode Island who claimed the National Marine Fisheries Service could not impose a fee requiring federal observers on herring boats, based on the applicable law.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that for 40 years, Chevron deference has served "as a cornerstone of administrative law, allocating responsibility for statutory construction between courts and agencies."

"This Court has long understood Chevron deference to reflect what Congress would want, and so to be rooted in a presumption of legislative intent," wrote Kagan, who was joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. "Congress knows that it does not — in fact cannot — write perfectly complete regulatory statutes."

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson joined the dissent in one of the two cases but was recused from the other because she took part in it as a federal appeals court judge.

Going forward, federal agencies will be under greater scrutiny, giving industry actors more opportunities to challenge agency rules and interpretations of the law, lawyers said.

"The decision could be viewed as putting regulated communities on a more equal footing with the agencies," said Varu Chilakamarri, a partner at the law firm K&L Gates.

The stakes appear to be particularly high for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The CFPB has a reputation as being more aggressive than some other federal agencies, and during the Biden administration, the bureau has found its rules routinely challenged in court.

The CFPB said Friday that it is reviewing the ruling and declined to comment.

The CFPB's interpretations of laws will now be subject to "heightened attack," said Joe Lynyak, a partner at Dorsey & Whitney.

"Courts around the country may be inundated with private parties who may now litigate and relitigate an agency interpretation, including creating conflicting decisions by lower courts," Lynyak said.

Eamonn Moran, senior counsel at Norton Rose Fulbright, said the rollback of Chevron deference may result in the overturning of regulations such as the CFPB's $8 credit card late fee rule. But he also cautioned about potential downsides for banks.

"While there may be now more opportunity for the plaintiff's lawyers to try to undo regulations through court challenges, industry may now be faced with lack of predictability and compliance challenges," Moran said.

Leah Dempsey, co-chair of the financial services practice at the law firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, pointed to what she described as challenges for regulated companies stemming from the court's decision, in addition to the opportunities.

In an interview before the decision was released, Dempsey said that companies are always looking for clarity on how to operate, and argued that the demise of Chevron could limit the ability of agencies to provide such clarity.

Kate Judge, a professor at Columbia Law School, wrote in a social media post that banks, like many businesses, "may see Chevron's fall as a win, but the Chevron doctrine was central in facilitating deregulation."

"The result today does not mean less regulation; it just ensures more uncertainty about the obligations the law imposes on regulated entities," Judge wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Joann Needleman, an attorney at the law firm Clark Hill, noted that many laws that affect the financial services sector are decades old, so they don't provide clear guidance about how companies may use newer technology. It has long been up to regulators to fill in those gaps.

Needleman said that following the demise of Chevron deference, she can foresee litigation by consumer advocates challenging rules that the CFPB established regarding the use of modern communications technologies by debt collectors. The CFPB's 2020 rule implementing the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act addresses the use of email and text messages by debt collectors. Advocates have opposed parts of the regulation.

Needleman, who is a former president of the board of directors of the National Creditors Bar Association, said in an interview before the court's decision was released that the CFPB's rule provides a modern interpretation of a decades-old law.

"A lot of what the CFPB did around that regulation was really helpful," she said.