- Key insight: WomenVenture, a Minneapolis-based Community Development Financial Institution, has assisted 108 small businesses seeking emergency assistance as federal immigration enforcement operations strain revenues and workforces across Minnesota.

- Forward look: The organization is establishing an emergency rapid response fund with other Minnesota CDFIs and community foundations, while navigating uncertainty around the CDFI Fund, which provides critical capital to community lenders.

- What's at stake: The unrest in Minneapolis comes as CDFIs across the country are strained as the Trump administration has stalled disbursements and awards through the fund.

LeeAnn Rasachak has some experience navigating crises.

Rasachak, CEO of Minneapolis-based Community Development Financial Institution WomenVenture, was already helping her customers and community weather the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 when the death of George Floyd spurred unrest across the city. The city's climate also means it gets its fair share of winter weather disruptions every year.

But none of those challenges have been as difficult to weather, she said, as Operation Metro Surge, the federal government's unprecedented influx of immigration enforcement into the state that resulted in high-profile deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti at the hands of federal officers.

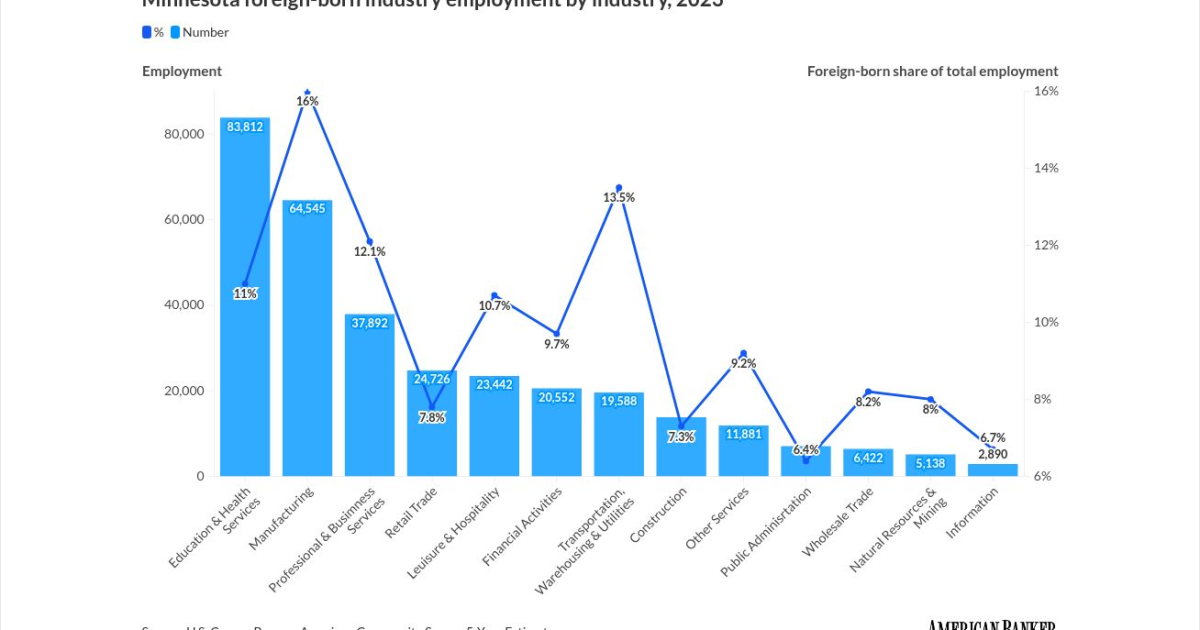

"It's across Minnesota that's been hit," Rasachak said. "Yes, the core of it is happening in the Twin Cities metro area, and yet the presence of Operation Metro Surge isn't just in the Twin Cities metro — it's happening in St. Cloud, which has a very large Somali community; it's happening in Rochester. You're seeing it across the map in Minnesota."

For those like Rasachak, who works closely with many small businesses across the state — from child care businesses to food service — the last few months have been a trial, she said.

"Particularly our immigrant-owned small businesses, and any business that have immigrants or people of color as part of their communities, myself included," said Rasachak, who

Sales revenue at many small businesses is declining, she said, as businesses face twin challenges of falling foot traffic and, in some cases, labor shortages spurred by immigrant workers being taken into federal custody or staying home out of fear of being deported.

"People are fearful, they don't want to leave their homes, they don't have people that are showing up to work," she said. "I talked with a snow removal business owner last weekend — less than half of his crew was present."

In response, WomenVenture has serviced 108 small businesses seeking help this year. The organization continues operating its core business training, consulting and capital access programs while also mounting a multi-pronged response to the crisis.

The organization is helping those whose loans may become delinquent, offering technical business assistance, loan modifications and payment deferments, Rasachak said. WomenVenture's books are currently healthy, she said, although if the crisis continues for three to six more months, it could force the CDFI to make difficult decisions.

The challenge facing community lenders extends beyond the immediate crisis in their communities. The CDFI Fund itself, which provides critical capital to organizations like WomenVenture, has

Graham Steele, a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute who oversaw the CDFI program under the Biden administration as the Treasury Department's assistant secretary for financial institutions, said the dual challenge of the small business crisis in Minnesota and the attempted dismantling of the CDFI Fund creates a particularly difficult situation for these kinds of community lenders.

"This is the mission that these institutions have: to serve the kinds of communities that are feeling the impact of this immigration enforcement," he said. "I will also say, this is a modern version of the legacies of disinvestment, and why the CDFI program itself was passed into law.

"These are communities that are disinvested from in good times, then during civil unrest, larger institutions decide they are risky and don't want to invest in them more," Steele concluded.

Carl Swanson, a strategist at the Minneapolis CDFI Coalition, echoed Rasachak's assessment that the impact of the immigration enforcement surge is affecting communities across the state.

"It's very real and happening in real time," Swanson said.

Some businesses have seen sales drop 90%, and construction work on affordable housing projects funded by CDFIs has been stalled because project managers have to develop and implement safety plans for workers, he said.

"Even if we do see a drawdown, business won't return to normal any time soon, because we already have the harms of people being taken, and it will take a long time for people's trust to be rebuilt," Swanson said. "It's not like this is a switch that gets turned back on."

Despite the crisis — or perhaps because of it — Rasachak has seen remarkable community resilience. On

"They opened to provide medical response, medical support, a place where you can go and have [yourself] taken care of because you have tear gas, where you may be hurt," Rasachak said. "They provided a safe haven where there's food, there's water, there's restrooms, there's warmth."

Large companies headquartered in Minnesota, including Minneapolis-based U.S. Bank,

Rasachak said that WomenVentures, as well as other CDFIs, are going to need an influx of support from large banks' and financial firms' philanthropic arms to continue propping up Main Street businesses.

"We need the heavy hitters to help continue to support the work, not just behind the scenes, but on the front lines," Rasachak said. "Activate your policy people, activate the pieces that are really going to make a significant economic movement for us. Because our state's in a crisis."

She emphasized that the economic consequences will affect "all income levels."

"Talking with those that go to private country clubs, they're seeing it in their workforce as well," she said. "There is no one that will be unaffected by this."

Without relief, business closures will mount, Rasachak warned. Some immigrant-owned businesses have already closed permanently, and others could face closure within 30 to 60 days.

Still, Rasachak said she's committed to seeing the community through its latest crisis.

"We've been around for nearly 50 years, and I have every confidence in the world that we will continue to do the work that we do, so that we can be around for the next 50," she said.