- Key insight: Banks have been lending to nondepository financial institutions at a rapid pace, but the Trump administration's approach to regulation could change their incentives.

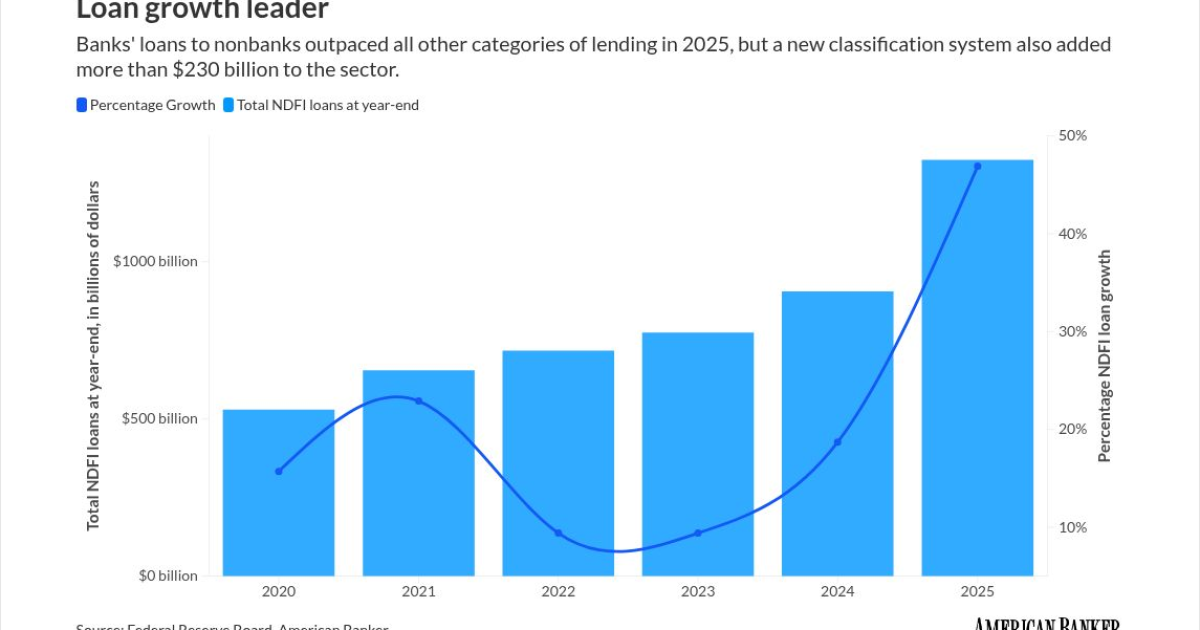

- Supporting data: Lending to nonbank financial institutions accounted for about 40% of bank loan growth in 2025, though the category only represents about 13% of total bank loans.

- What's at stake: A series of credit cracks this fall raised questions about the safety of the sector. Bank executives caution against painting with a broad brush.

Following a year that highlighted the growing risks in bank lending to nonbank financial institutions, a key question has become: Does 2026 portend credit deterioration or a retreat from the sector, as regulatory changes clear a path for banks to slow the pace of their activity?Over the last year, the growth in bank lending to nonbanks — such as private equity and private credit funds, mortgage originators and insurance companies — outpaced every other loan category.

The sector made up roughly 40% of all U.S. bank loan growth since January, according to Federal Reserve Board data, analyzed by American Banker.

Julie Solar, group credit officer for North America Financial Institutions at Fitch Ratings, said the risks of private credit aren't systemic for the banking sector, but she also argued that opacity may obscure any deterioration of underlying borrowers' performance.

She added that if there's heat, smaller banks will likely feel it most acutely, since the larger banks are diversified and big enough to absorb losses.

"There are going to be banks that have grown their exposure to this asset class too fast, that are overly concentrated right now," Solar said. "There are going to be some banks that have tall trees in their portfolios that will suffer losses, that will run into potentially solvency issues."

'Cockroach' autumn

This fall, more than half a dozen banks posted higher chargeoffs or provisions for losses in connection with several separate nonbank borrowers that went belly-up — the subprime auto lender Tricolor Holdings, the auto-parts maker First Brands Group and two entities associated with real estate investment firm Cantor Group.

The banks involved claimed that each incident was a one-off, all allegedly due to fraud, though JPMorganChase CEO Jamie Dimon warned that "one cockroach" could be a sign of more.

The revelations about individual banks made some investors nervous. During the period when the incidents became public, the Nasdaq Regional Banking Index dropped 11%, though it has since recovered and finished the year up 2.6%.

During earnings calls this fall, bank executives spoke about what they saw as a disconnect between the safety of their nonbank loans and how investors were viewing them.

And to combat jitters in the market, many banks provided additional disclosures about their lending to nondepository financial institutions, or NDFIs, during quarterly earnings calls in October.

"As the analyst community has learned, when you look at that category on a call report, not all NDFI lending is created equal," Customers Bancorp Chief Financial Officer Mark McCollom said on the bank's earnings call.

About one-third of the $24 billion-asset bank's total loan book was made up of nonbank loans, McCollom said, comprised mostly of fund finance, mortgage warehouse and lender finance business.

U.S. Bancorp supplemented its latest earnings presentation with an additional slide that detailed the composition of its nonbank loan exposure. Chief Financial Officer John Stern said in October that the Minneapolis company wanted to highlight that not all nonbank lending carries the same level of risk.

Mark Mason, the finance chief at Citi, said during the megabank's third-quarter earnings call that investors should evaluate the quality of banks' nonbank lending portfolios, rather than their size.

"We're very selective from a risk perspective as to how we play across all of these subcategories, but particularly as it relates to private credit," Mason said. "And I think the key takeaway is that that category is very broad."

Revising disclosure rules

Last year marked the start of a new Fed protocol for filing call reports, which expanded the definition of NDFI loans. The rules, which were designed to increase the granularity of reporting and improve the consistency of banks' nonbank lending data, took effect at the start of 2025, affecting banks with $10 billion of assets or more.

The revised system defines nondepository financial institutions as financial entities that provide similar services as banks, but don't accept deposits and aren't regulated by federal banking agencies.

Banks must separate, across five categories, loans to: mortgage credit intermediaries, business credit intermediaries, private equity funds, consumer credit intermediaries and other nondepository financial institutions.

Bankers and analysts alike have raised concerns about the new classification system.

Based on the reported data, the volume of bank loans to nonbanks grew by some 50% between 2024 and 2025. But when the data is adjusted to account for loans that were reclassified from other categories to meet the updated reporting standards, the annual rise is more like 20% to 30%, according to analysts.

"I think the classification [change] was well meaning, but not the best execution," said Brian Foran, an analyst at Truist Securities. "The categories are still pretty broad. … So it's still an area that's a little opaque, a little frustrating."

Matthew Bisanz, a lawyer at Mayer Brown who focuses on bank regulation, said the categories aren't clear enough to banks or investors. He worries they may cause the market to misunderstand banks' operations.

Tim Spence, Fifth Third Bancorp's CEO, said in an interview following his company's October earnings call that "nonbank lending" isn't a very meaningful descriptor, due to the category's breadth. He said loans to Fortune 500 payment processors and insurance companies are quite different, from a credit perspective, than warehouse activity and loans to real estate-linked businesses.

Fifth Third was one of the banks caught up in the Tricolor credit drama, logging a $200 million hit.

Spence said that he thinks the Fed will eventually refine its guidelines around nonbank loan reporting, but that until then, banks should provide more clarity about the breakdown of their exposures.

Impact of Trump-era regulatory shifts

The $2.5 trillion-plus NDFI sector has been steadily growing for nearly two decades.

After the financial crisis of 2007-2009, new rules for big banks, including certain capital requirements, reined in banks' lending capabilities, Foran said. In response, traditional lenders have been doling that money out to nondepository financial institutions, which in turn make the loans that the banks can't.

The practice can offload risk from banks' balance sheets. But analysts wonder how much wallet share traditional financial institutions are giving up as their competitors take on the direct relationship with borrowers.

Foran said he worries that banks are disintermediating themselves.

"The real crux of the investor worry is, 'How much are banks being incentivized to do these special purpose entities, which then a private credit fund can then use to make loans that banks otherwise would have?'" Foran said.

Through supervisory exams, the Fed has more visibility into banks' lending practices than the public does.

In its latest Financial Stability Report, published in November, the Fed found that most nonbank borrowing was in the following categories: special purpose entities, collateralized loan obligations and asset-backed finance; private equity and private credit; and real estate lending.

And despite the surge of nonbank lending in 2025, the category still makes up only about 13% of total bank loans, and is concentrated among the largest banks.

Investors and banks are hopeful that certain changes in the regulatory regime and economic landscape will open the door for banks to take back some business they may have had to forgo in recent years.

Michelle Bowman, the Fed's vice chair of supervision, said in June that certain post-financial crisis regulations drove "foundational banking activities out of the regulated banking system and into the less regulated corners of the financial system." She questioned whether such rules were appropriate.

Earlier this month, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. rescinded 2013 interagency guidance on leveraged lending, saying it was "overly restrictive and impeded" banks' businesses.

"This resulted in a significant drop in leveraged lending market share by regulated banks and significant growth in leveraged lending market share by nonbanks, pushing this type of lending outside of the regulatory perimeter," the agencies said in a release.

Truist Securities' Foran said he doesn't expect the regulatory changes to be a watershed for a pickup in direct lending by banks. But he does think the rapid pace of growth in nonbank lending could start to slow.

Solar, of Fitch Ratings, expects that banks' risk appetite will broaden alongside the regulatory shifts.

"Presumably, it's going to lead to greater competition," Solar said. "Potentially the banks might participate more than they would have in the past, particularly in the large sponsor-backed transactions, potentially holding larger positions, potentially at a higher leverage multiple than they would have in the past."