Back in 2016, this writer authored a number of research papers and reports that examined the differences between depositories and finance companies in terms of the sources and uses of capital. This effort responded to a dangerous trend in the public policy debate on independent mortgage banks that focused on concepts and benchmarks more appropriate to commercial banks.

Finance companies, after all, are part of the private sector, while banks are government-sponsored entities that enjoy numerous public subsidies and the monopoly protection of the Federal Reserve Board over the U.S. payments system. If you are not an insured depository, then you are a customer of a bank.

Nonbanks are dependent upon banks for financing. This group includes all IMBs and, of note, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The fundamental economic difference between banks and nonbanks colors the conversation that proceeds from the question: How much capital does a non-bank mortgage company need?

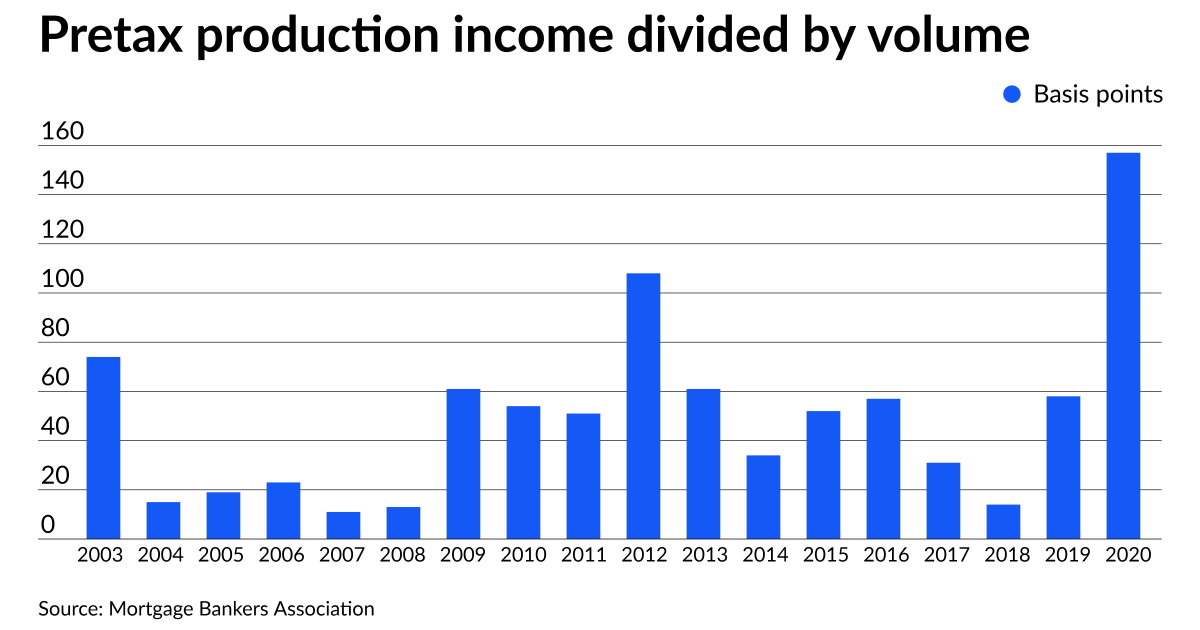

Banks hold capital as a source of strength, if for no other reason than to reduce the cost of resolution to the FDIC’s bank insurance fund. Banks have capital to absorb credit losses. Nonbank finance companies, on the other hand, have levels of working capital that are correlated to interest rate movements. The chart below from the Mortgage Bankers Association shows pre-tax production income divided by loan volume in basis points.

IMBs do not have the ability to absorb significant losses. Properly understood, IMBs are sales networks that often buy rather than make loans, then sell these loans to investors. IMBs enable an ecosystem of correspondents and wholesale brokers that have one purpose, to make loans and sell them into the secondary market as quickly as possible. Banks are about maintaining capital, but non-banks are about maximizing asset turns.

It’s no accident that commercial banks like Western Alliance Bancorp (NYSE:WAL), which acquired hyper-efficient aggregator AmeriHome, or American Express (NYSE:AXP), trade at a premium to other banks in the equity markets. Why? Because they have finance company DNA flowing through their veins. These banks maximize asset turnover and thus the use of capital, generating outsized equity returns.

Most commercial banks, on the other hand, are deliberately made dysfunctional via regulation to avoid risk and especially the risk of facing consumers directly. Commercial banks have fled direct exposure to the Federal Housing Administration, Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Agriculture markets in the past decade, but at the same time, they increased wholesale exposure to IMBs via warehouse and advance lines.

Bank credit lines to IMBs are fully secured by government-insured, conventional or private loans but isolate the bank from facing consumers, who are rightly viewed as being toxic in terms of reputation risk. Commercial lending is a better business for banks, a fact reinforced by prudential regulators since the 2008 financial crisis.

IMBs, for their part, are far more efficient than banks operationally and better able to service one-to-four family loans without running afoul of state or federal regulators. A decade since the 2008 crisis, the partnership between commercial banks and IMBs seems to be in balance. Banks provide financing to the wholesale mortgage finance business and IMBs make and service the loans. Indeed, IMBs often sell loans to commercial banks.

Over the past several years, first the Financial Stability Oversight Council, then the Federal Housing Finance Agency, then the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, have threatened IMBs with ill-informed capital rules designed for banks. These rules, including for the GSEs themselves, ignore the major economic and financial differences between a bank and a finance company.

Hint to all of the above agencies: If a regulation does not work economically, then it is probably not going to work as public policy either.

Most recently, Ginnie Mae has threatened IMBs with new eligibility requirements that would severely cut leverage and profitability in the government loan market. This change will decimate government lenders and greatly reduce the value of mortgage servicing assets. I addressed this proposal in a recent blog post in The Institutional Risk Analyst.

The issue raised by the Ginnie Mae rule as well as the eventual capital rule for conventional issuers coming from the FHFA is this: How much capital does a mortgage bank really need?

Most IMBs actually operate with net negative working capital, especially those shops with high asset turns. Banks provide this capital in the form of secured and unsecured debt. Since the objective of IMBs is to make and sell loans, including loans that come off of their servicing book, IMBs don’t want or need to build excess capital. And the equity markets are not interested in providing IMBs or even the GSEs with bank-like levels of capital.

IMBs have some long-term liabilities, but the operational ability to make and service loans profitably and the financial capacity to retain mortgage servicing rights are the two key attributes of a successful mortgage bank.

As the servicing book of an IMB grows, more and more business can be generated internally, greatly enhancing issuer equity returns and the stability of the business. A big servicing book is good for IMBs.

For regulators, the key assessment for IMBs in terms of liquidity needs to be a simple net worth test that is closer to that used by the SEC and FINRA for broker dealers than for commercial banks. The IMB must have sufficient net capital to support its loan book and MSRs, including financing timely interest payments to bond holders. Warehouse lines and particularly term debt should be counted towards fulfilling liquidity needs.

One key aspect of this analysis for both Ginnie Mae and FHFA should be how much of the servicing rights the IMB retains. Servicing a performing loan costs a few basis points, but servicing a distressed loan can cost more than the servicing fee and can continue for months and months. Ensuring that IMBs retain sufficient portions of the servicing strip to cover operational or credit expenses incurred as part of loss mitigation is critical.

Instead of trying to impose bank capital rules on finance companies, regulators at FHFA and Ginnie Mae should instead take steps to maintain minimum liquidity. Back in November of 2018, prior to the sudden departure of Ginnie Mae President Michael Bright, the agency issued a new rule to participants (APM 18-07) requiring IMBs to report sales of participations in or entire MSRs to investors.

“To promote stability and liquidity in the secondary market, Ginnie Mae is implementing a series of updates to its counterparty risk management framework to strengthen the financial resilience of Issuers,” Ginnie Mae announced. Nothing has been heard of the program publicly since that time, but it remains an important template for Ginnie Mae and the FHFA to consider enhancing.

Both FHFA and Ginnie Mae would be well served by putting aside draconian bank capital rules and instead focus on a simple regime for capital and liquidity that enables the IMBs to make and sell loans. Here’s another hint for regulators: As profitability declines, so will IMB capital, making access to bank credit and debt markets crucial. Don’t set static capital levels for IMBs when you know the tide is going out. Call Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell with any questions.

By focusing on things that matter, like maximizing operational efficiency and profitability, plus monitoring sales of servicing income to investors, regulators can ensure a robust nonbank market for lending and servicing, and also protect the commercial banks that support the mortgage finance market. But don’t try to pretend that IMBs or even the GSEs are commercial banks. That is a fool’s errand that will end in tears.