The

Although banks have been making those loans for decades, the confluence of watershed legislation in 2019, rising interest rates and inflation has made it more difficult for landlords and property managers to turn a profit, said Wedbush Securities analyst David Chiaverini.

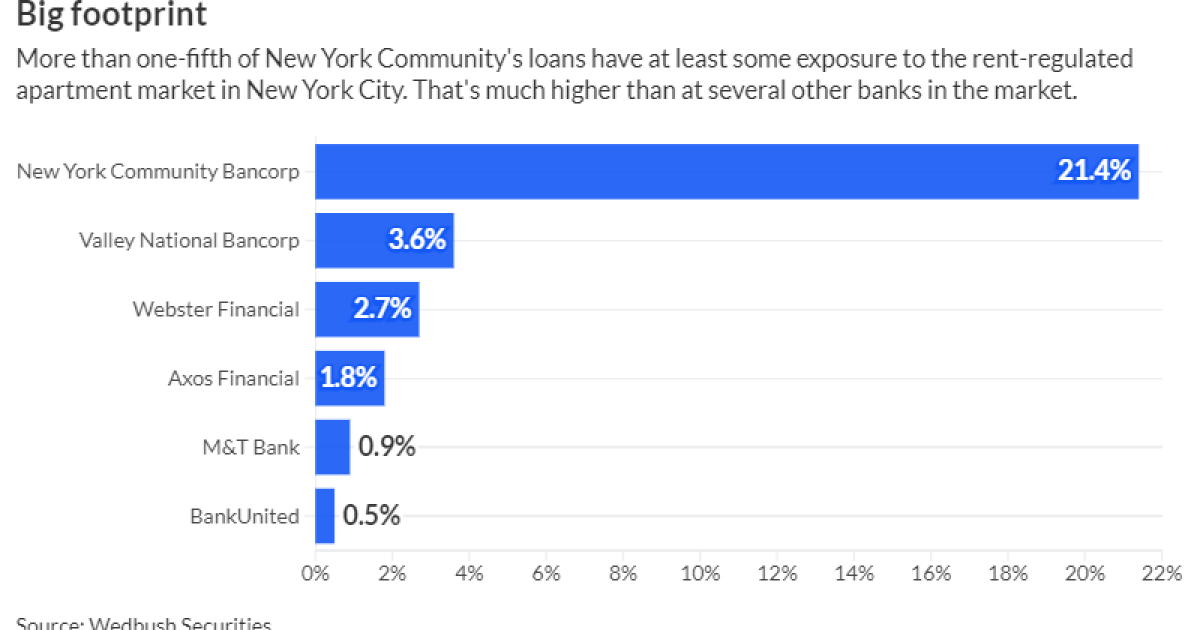

New York Community's concentration in the sector makes it an outlier among regional banks. Roughly one-fifth of all loans held by the Long island-based bank are exposed to the New York rent-regulated multifamily market, according to Wedbush.

New York Community built its business with landlords and property owners in the rent-regulated sector over the course of decades. But recent challenges, including an unexpected dividend cut and a

As of Dec. 31, 2023, about 6% of the bank's $81.6-billion loan portfolio was made up entirely of rent-regulated multifamily loans, the bank said in its latest earnings report.

"The good news is that this is very much unique to New York Community Bank in terms of the outsized exposure that they have to this asset class," Chiaverini said. "The 2019 regulation laws that became more onerous, combined with interest rates having gone up as much as they have — that double whammy is what led to the most recent quarter's surprise in terms of how much [New York Community] needs to set aside."

At the end of last year, New York Community reported that it had about $18.3 billion of loans with rent-regulated exposure, about 14% of which were categorized as being at risk. In the fourth quarter, the bank took a $552 million provision for credit losses, up from $62 million in the previous quarter.

Since 2019, rent-regulated property valuations in New York City have been cut in half, said Seth Glasser, a multifamily real estate broker at Marcus & Millichap. The Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act, passed in New York state that summer, was a turning point for rent-regulated properties, according to Glasser. The law capped rent increases, limited the size of returns that landlords could earn for making renovations and eliminated eviction plans, among other provisions.

Chiaverini said the five-year-old policy is squeezing net operating income at some rent-regulated properties, making it harder for borrowers when those loans mature in a higher-rate environment. While the costs of renovating and maintaining properties have increased, and rates have roughly doubled, rent increases have been forbidden, Glasser said.

New York Community's

Borrowers may not have the cash to pay down the principal on the prior loan, or to inject more equity into a refinanced deal, he said. That leaves banks to choose between bad options, including providing below-market-rate loans to their borrowers and potentially taking losses by foreclosing when property values are down.

Glasser said that selling the loans isn't a great option either, because decreased proceeds and higher rates mean that such transactions would require steep discounts.

"The banks are saying, 'We're not taking haircuts on our loan. We want 100 cents on the dollar or 95 cents on the dollar,'" Glasser said. "But no one's willing to pay 90-plus cents … so none of the notes sell."

Chiaverini said he also doesn't see loan sales as a viable option because of the discounts required for those transactions.

At New York Community, Chiaverini expects the situation to play out slowly. More than 80% of the bank's loans on buildings in which all of the units that are rent-regulated will mature in 2025 or later, giving the bank time to build its reserves, he said. He expects the bank's first-quarter numbers to be less messy, though he added that it's a "low bar" in comparison with last quarter.

New York Community's stock price fell another 23% on Monday after the bank's ratings were downgraded on Friday by Fitch Ratings and Moody's Investors Service.

"New York Community, as opposed to seeing that outsized provision that they put up in the fourth quarter, they will gradually build the reserves, quarter by quarter," Chiaverini said. "It won't be a shock to the stock, but I think it'll be a headwind to the stock appreciating significantly in value, because other banks that aren't having this issue will be growing their earnings."

New York Community did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

At Valley National Bancorp, Webster Financial and Axos Financial, which also lend in the space, less than 4% of their total loan portfolios touch rent-regulated property. Banks have been pulling back from rent-regulated real estate lending, but those that are in the sector will be more conservative, likely decreasing their loan-to-value ratios, Chiaverini said.

Travis Lam, deputy chief financial officer at New Jersey-based Valley, said the bank

Valley's entirely-rent-regulated portfolio is $420 million, or less than 1% of its total loans. Some 3.6% of the bank's loans have a small portion of rent-regulated exposure.

"The reason that we only have $420 million of rent-regulated multifamily exposure is not necessarily because we have a view on the credit," Lam said. "It's because we're not competitive with some of the more aggressive players in the space from a pricing perspective, because we're conservative in the way that we underwrite."